Marks Ending : Codex Aleph (Sinaiticus)

Marks Ending Codex B (Vaticanus 1209)

EXTRA LINK

"...

Jan suggested to work with two dimensions in the classification: problems and causes. I immediately knew that was it! But how does that work, a classification with more than one dimension? I started to study the theory of classification, and I realized I had always been restricting myself to a certain form of classification, namely a taxonomy.

In a taxonomy, an object can occupy only one place in a hierarchical system: classifying a dog in a taxonomy of animals means positioning it at one of the branches of a tree, by means of characterizing it according to certain variables which are considered in sequence.

However, there is also a more complex form of classification: a typology. An example of a typology would be the characterization of a group of people according to their gender as well as to the colour of their hair. Each individual is not positioned within a hierarchical structure, as in a taxonomy, but characterised according to two variables that are considered in parallel, instead of in sequence.We needed a typology! The argumentation for each conjecture necessarily has two dimensions, the detection of a problem (in the transmitted text) and the suggestion of a cause of the supposed corruption (that is, a certain type of scribal error/change). ..."

|

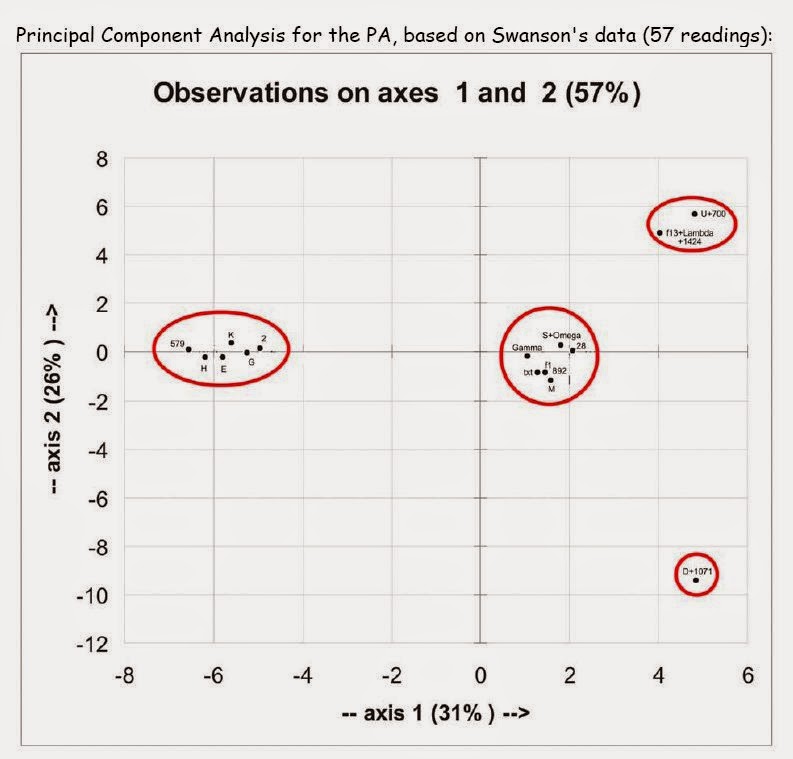

Example: Willker's Principal Components Analysis |

"But again and again some conjecture popped up that posed a problem and called for an adjustment of categories or definitions. Interestingly, most of the time such adjustments made the classification more straightforward, often making me wonder why that didn't occur to me earlier. ..."If early Textual Critics were given another chance at reconstructing the NT text, would they be able to adapt and embrace the more modern and multi-dimensional view of today, and reassess the crude and (in hindsight) misleading 'guidelines' of Textual Criticism of the 19th century?

"Amongst the many mistakes in the manuscript particular attention - so far as this edition of Enoch is concerned, - should be drawn to the existence of numerous omissions, many through homoioteleuton..." - The Ethiopic Book of Enoch, Michael Knibb, p. 17,(1978, Oxford Press) |

|

| Click to enlarge: backbutton to return |

Tommy's excellent presentation on the text of Mark 1.1 is now available in audio via the CSCO website (where it is also described as argued persuasively):In his analysis, Tommy Wasserman notes that there are either 6 genitive endings of words in a row, or else 4 Nomina Sacra, creating an easy situation for error. In his opinion, the argument that omissions are unlikely in the very beginning of a book is outweighed by both the textual evidence and the intrinsic evidence regarding Mark's style and purpose.

Tommy Wasserman, ‘The “Son of God” was in the Beginning,’ lecture (44min)

Wasserman, Question and Answer, (28min)

" The further blanket claim that I “ascribe error and scribal slips to all the errors of Aleph & B” is simply incorrect. While I do maintain (on the basis of a careful examination of scribal habits) that scribal error is a primary cause of textual variation, I also clearly presume deliberate alteration and recensional activity to have occurred among the Alexandrian manuscripts (as per my 1993 article, “The Recensional Nature of the Alexandrian Texttype”). The leading principle in this regard is to presume scribal error as an initial factor so long as transcriptional probabilities suggest such, then to presume intentional change at whatever points transcriptional probabilities seem to be transcended for what appear to be stylistic or content-based “improvement” concepts in the eyes of particular scribes.I trust this will clarify the matter."

"To illustrate these [accidental errors], one or two instances under each head are selected from Mr. Hammond's recent convenient little manual (Outlines of Textual Criticism applied to the New Testament. By C. E. Hammond, M.A. Oxford : Clarendon Press. 1872. From this work much of the present paper has been abridged.)

Under errors of sight belong omissions from what is technically called Homoioteleuton. Thus, in Codex C, the words τουτο δε εστιν το θελημα του πεμψαντος με are omitted in John 6:39, because the last three words had occurred immediately before, and the eye of the scribe passed on from their first to their second occurrence. This happens especially when the same words occur at the end of consecutive lines.

To the same head belong the many instances, more generally in the uncial MSS., arising from the confusion of similar letters such as Α, Λ, Δ ; or Ε ς, Θ Ο. From this arose the well-known and well-disputed reading in 1 Tim. 3:16. Similar letters or syllables are sometimes omitted and sometimes inserted; thus in Matt. 26:39 for ΠΡΟΣΕΛΘΩΝ Cod. B has ΠΡΟΕΛΘΩΝ, and in Luke 9:49 Cod. H has εκβαλλοντα τα δαιμονια for εκβαλλοντα διαμονια . Letters, too, are sometimes transposed, so that in Acts 13:23 for ΣΠΑΙΝ, Codd. H and L read ΣΠΙΑΝ {σωτηρα Ιησου} . The number of errors from this source is very large, as the margin of any critical edition will readily show."